When I’m walking in the mountains or the countryside, my mind has time to drift freely and unhurriedly into random topics. It’s one of the great luxuries of our current lifestyle. Sometimes I find myself burrowing deep into a particular topic, and I can even feel a euphoria of imagined insight.

In northern Wales, I had a burrowing walk, contemplating what it means to walk. Or hike. Also see: ramble, trek, scramble, etc.

To thump our collective chest a wee bit, we’ve got a lot of raw data on this topic—first-foot experience of nearly 1,200 miles of trails over the past 16+ months in deserts, bogs, forests, charred lavascapes, snow fields, and denuded sheep-shit-strewn pastures; through and around lakes, along and across streams, cliffs, jagged coastlines and sandy beaches; amid giant old-growth trees, tall wildflowers, tiny alpine rock-hugging plants, lichens, moss, biological soil crust, scruffy heather, and gorse; in blinding sunlight and sodden fog; strolling on wide flat paths, wedging footholds amid roots and rocks, and scrambling up bouldery crags.

I could keep listing—it’s so much fun. Nature’s variety astounds and inspires. What is beauty? It takes so many forms that I can’t tell you. But I know it when I see it.

As Bob mentioned in our last blog, we’ve been in the United Kingdom since the end of June. It is amazing country for hiking, due to the sheer abundance of footpaths branching out from every village. And many–but not all–Brits are enthusiastic about enjoying this resource. In his book, Under the Tump, Ollie Balch (a new friend in Hay-on-Wye), reported a conversation with a local farmer who groused about outsiders flooding into the rural areas to walk the public footpaths. After all, the paths were not made for recreational enjoyment but for people to go conveniently from one place to another.

I heartily second Bob’s recommendation that you listen to a recent 99% Invisible podcast on the a history of public footpaths and the “right to roam” in the UK. It also speaks volumes about the radically different views of private property rights in the US and the UK.

Walking: How Hard Can That Be?

For me, there are nine principal variables which determine the difficulty of a hike (walk):

1. The elevation (is there enough oxygen?)

2. The scenery (will I be rewarded for my efforts or is it a pointless slog?)

3. The gradient (how steep is it? Will my knees be suffering?)

4. The ascent/descent (how far will I have to climb up/down?)

5. The distance (how long will I be doing this?)

6. The weather (am I going to freeze, overheat, get drenched, or be blown over?)

7. The quality of the signposting (will I lose my way?)

8. The quality of the trail (is it muddy, rocky, rooty, all of the above, or no trail at all?)

9. The presence of biting insects (enough said)

In Britain, you obviously don’t have a problem with altitude sickness, and the scenery is almost always lovely. But the other seven variables can be WICKED!

First, about language. If an outing requires the use of hiking boots, I call it a hike, whereas I think of a walk as something you do on flat ground or on pavement. In the UK, the word hiking is seldom used. Instead, what I call hiking is just referred to as walking, or hill-walking. Mountaineering, on the other hand, is what we generally call climbing and often entails ropes and carabiners. (Note: We are definitely not climbers or mountaineers!)

Don’t let the word “walk” throw you off. A walk in the UK can be very challenging. In addition to beautiful pathways, it often includes slogging through spongy bogs.

Our favorite online Scottish walking guide (www.walkhighlands.co.uk) includes a “bog factor” rating among its data points provided for every walk. It uses a scale of 1-5 reedy puddle icons, with 5 puddles meaning “It’s a swamp. Snorkel recommended.” We avoid those. (As an aside, during our month in Hay-on-Wye, we missed, by one week, the nearby 33rd Annual World Bog Snorkeling Championships. So disappointing!)

British walks are typically done uprIght, except when they devolve into “rough” or “full-blown” scrambling over bouldery bits where you need to use your hands as well as your feet. We had some good scrambles while hiking in the US—Estes Cone near Estes Park, Colorado, comes to mind, as does the ascent to the Sahale Glacier in the North Cascades. In the UK, many of the highest mountains require scrambling in the final approach to the summit. When we climbed Mt. Snowdon, the highest peak in Wales, we chose to use a less-traveled route for our ascent that is described as “one of Britain’s most epic walks” but also as a “full-blown scramble.” It was a foggy drizzly day, with limited visibility, and the scrambling was so full-blown and epic that I thought that I had seriously overplayed my hand and was probably going to die. This was scrambling on steroids: sheer (wet) rock faces with scattered hand- and foot-holds, and a long (wet) knife-edge ridge that I had to take on all (wet) fours for an uncomfortably long time. I learned that looking to the left or right was bad for me because it reminded me that the ridge plunged off into mysterious white nothingness on both sides.

My heart pounds even as I reflect back upon that scramble, but having survived it, we can say we were glad we took that route. As we neared the summit, our path converged with the three or four main paths where we joined a massive human throng, a crazy foggy pilgrimage.

I don’t care what you call it: I find that walking or hiking is best done with as few people as possible. On Snowdon’s summit, there were about a thousand people too many for my taste. We’ve never seen anything remotely like it and hope never to do so again.

How to Not Get Lost

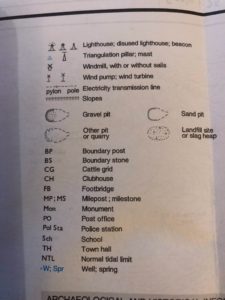

Topographical (“topo”) maps are considered a must for hiking, because they illustrate trails, elevation changes and other geographical features that aren’t shown on a road map. They’re very helpful and fun because they prompt you to imagine all the things that are around you that you can’t see. In the US, you typically can only buy topo maps in outdoor gear stores or park visitor centers. Sadly, they are also getting woefully out-of-date. In the UK, “ordnance survey” (OS) maps are sold everywhere, down to the humblest convenience store, and everyone moving around the country seems to use them. They come in various scales (i.e. 1:25,000 or 1:50,000) and can be amazingly detailed, showing fences and the stiles you can use to cross them, where streams can be forded, the names of houses, locations of cairns, levels of bogginess or stoniness, and even helpful hints.

Our favorite trail hint, on a map on Exmoor, in southwest England: “Used to go down.” Bob interpreted this as “there used to be a trail here.” We found it, and once we were halfway up it, we laughed when we realized the mapmaker was advising that the trail was so steep it should probably only be used for going down.

I confess I have tended to be a bit cavalier about topo maps, and have only recently disciplined myself to learn how to use them. I ascribe my laziness to the fact that Bob enjoys using his excellent map-reading skills…

…and also because in my (mostly US-based) hiking experience, trails are very well marked with signs or blazes. If you follow the markings and stick to the trail, it’s hard to get lost. If you’re into off-trail exploring, then your topo map-reading skills can mean the difference between a glorious adventure and a total disaster. A compass, a GPS, and a written narrative of the trail are also advisable, although again, while hiking in the US national parks, I mostly viewed these as safety nets rather than real tools that I actually needed to use.

I think we only encountered one or two examples of poor trail markings in the western US last year. The most memorable was at Ptarmigan Lake, in the Collegiate Peaks area of Colorado, where we and another couple struggled up to an adorable lake situated at 12,300 feet, using a trail that was only sporadically marked and surprisingly overgrown and blocked by fallen trees in places. We kept diverging and re-converging with the other couple, comparing notes, maps, and guidebooks, hiking up a stream bed in one section. We all knew something was very wrong but couldn’t tell what it was. As we began our descent, we were surprised to encounter a very obvious, excellent trail, and we took it. It was exceedingly pleasant and easy, with none of the drama and adventure of our ascent. It wasn’t until we got back to the parking lot that we realized we had started off initially on an old abandoned path. We never saw the trailhead to the new and improved path because a large summer camp bus was parked right in front of the trailhead sign, completely obstructing our view of it. We all laughed. Ah, nothing like a good trail funny!

In the UK, you should never, ever take your OS map and other navigation tools and skills for granted. Orienteering is a fundamental aspect of hill-walking, as much as the physical challenge and the scenery. (A memorable advisory we saw in Snowdonia: “You must have the proper tools and equipment AND know how to use them.”) While hill-walking here in the UK, we have experienced all of the following: been lost, confused, disoriented, had to turn back (only once), read the same paragraph over and over again and debated the nuanced meaning of comma placement, compared map readings to GPS, not been able to see more than 20 yards in front of us, and speculated on the meaning of such Welsh words as “bwlch”, as in “Continue on until you reach the bwlch, then turn left.”

So, gentle readers, do not snicker when you read about a “walk” in the UK that is for “experienced hill-walkers only.” That walk could get you into real trouble.

Elevation

I am conscious in this writing that many readers may scoff at the use of the words “mountains” and “peaks” for anything in the British Isles. Fair enough. The highest elevation in the UK is Scotland’s Ben Nevis, at 4,411 feet above sea level. Snowdon, the highest peak in Wales, comes in at 3,560 feet.

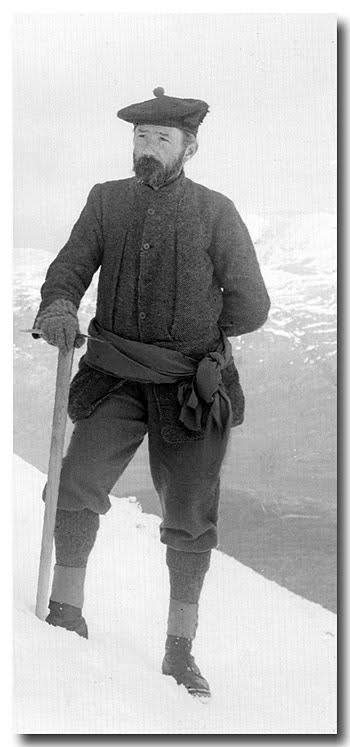

Nevertheless, Brits feel passionate about their hills, and “Munro bagging” is a favorite sport. Scotland has 538 summits over 3,000 feet, of which 282 are considered “separate mountains” and designated “Munros,” after Sir Hugh Munro who produced the first list in 1891.

If you want to bag Munros in Scotland, you must be able to differentiate your Munros from your Corbetts, Grahams, and Marilyns. To clarify, all Munros, Corbetts, and Grahams are Marilyns, but not all Marilyns are Munros, Corbetts or Grahams.

In contrast, Colorado has 53 peaks over 14,000 feet (“fourteeners”), and the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu goes up to 13,828 feet. Even the Munro Marilyns seem very tame by comparison.

But I rise to defend the peaks of Britain! Despite their relatively low elevation, the way up can be very exposed to high winds and wet weather and require lots of scrambling without a clearly marked trail. Since most of the climbs begin quite near sea level, a 3,500 foot summit actually means 3,500 feet of climbing. And the distances are short, so they are often very steep. We bagged Ben Hope in 2.5 miles, walking pretty much straight uphill. Bagging a Munro is no mean feat!

In comparison, the elevation gain on our ascent to Ptarmigan Lake last June was only 1,600 feet over 3.4 miles. Our hike to the amazing Sahale Glacier in the North Cascades in late August had a 4,000-foot elevation gain over 6 miles, ending at 7,600 feet.

We were surprised and a bit skeptical to learn that early British mountain climbers trained for Everest on Mt. Snowdon. It made more sense after experiencing it firsthand. Even so, I sure hope they practiced in other places as well.

In closing, I’d like to share a short creative work drawn completely from actual words and phrases found in a guidebook for hill walks near Penmachno, Snowdonia, in northern Wales—where we stayed at the lovely cabin of our friends Sachi and Quentin. We used poetic license in re-assembling the phrases.

To the Bwlch!

Enter a rough pasture with a broad tussocky ridge

Cross a wettish reedy area

Boggy and mucky

Go through a kissing gate

Pass a ruined farmhouse

Toward an old wall corner

Look for the gap in the wall

Walk along the embanked field edge and turn left at the bwlch.

In the distance, spot the trig point on a small rocky top

Pass through thistles, bracken, nettles, gorse and heather

To a narrow stony track

Cross a cattle grid and follow the field edge

Go through the small iron gate

And over a stone slab bridge

To an upland pasture

Keep south of the bwlch.

The main route meanders through a forest

On a delightful enclosed stony path

Turn left at the burn

Then head for a descending rough track

And join the river near stepping stones

Head toward the old tree boundary

Go over the ladder-stile and continue into open country

You will know you have arrived when you reach the bwlch.

What a sweet walk you just took me on, meandering through the language, the scenery and uphill to the Bwlch! Thanks for sharing. On to continuing adventures!

Fabulous!!! xxxx