Wherever we go, national parks seem to exert a magnetic attraction for us. We seek out opportunities to explore wild places, and national park status seems like a reasonable launch point for trying to find them.

While we spent eight months last year visiting 29 national parks in the western United States, we are by no means experts on the subject. But how a country attempts to conserve, protect, and nurture its natural resources, and how to strike the right balance between preservation and human recreation and other uses are topics of immense interest to us.

Having just spent nearly three months in the United Kingdom (the union of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland), we thought it might be interesting to share a few reflections on UK national parks from a “New World” perspective. Our UK experience also provided us with a new and valuable lens for viewing the United States’ park system.

There are 15 national parks in the UK, and we have visited ten of them.

Unlike in the US and other places we have visited, most of the land in the UK’s national parks is privately owned. Whole towns and villages exist within park boundaries, and it’s not unusual to share walking paths with grazing animals or to walk past recently clear cut stands of timber.

Indeed, it’s often difficult to recognize you’re in a national park as few landmarks distinguish it from surrounding landscapes.

History matters

This distinction stems in part from the fact that UK national parks were established relatively recently, in a part of the world that has had significant human settlements for at least 5,000 years.

England and Wales established their first parks in 1951. Scotland created its two national parks less than 20 years ago, and there are no national parks in Northern Ireland.

By contrast, the first national park in the US (Yellowstone) was established in 1872 during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The early years of the US national park system received an important boost from the passionate and visionary advocacy of Scottish-born John Muir. While it is true that even the most pristine-seeming natural environments have been altered by humans over millennia, Muir’s timely efforts as the western US developed helped to shield these environments from further impact, creating vast protected wildernesses that no longer exist in the UK or anywhere else in Europe. Incredible sweeping landscapes and jaw-dropping natural beauty yes; wilderness, no.

Local control

In the UK, each park is managed by a park authority (like a board of directors) drawn primarily from local representatives. The national treasury provides each park with a small budget, most of which goes to planning and public education. Each park authority is charged with preparing a five-year management plan and regulating land use.

Land use looked fairly permissive from our US perspective, but locals may see it otherwise. I spoke to a farmer in Scotland who complained of regulatory heavy-handedness. As an example, he said he’s no longer allowed to bury a dead cow on his farm—instead he must contact the park authority when a cow dies and have the carcass shipped to an incinerator many miles away. I’m sure there are other colorful examples.

What’s the point?

Legislation in England and Wales declares two purposes for the parks: conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife, and cultural heritage, and promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of national parks by the public. That’s not too different from the dual mission of the National Park Service in the US—to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. But UK park authorities also have a duty to seek to foster the economic and social well-being of local communities within the national parks. Scottish legislation goes further and declares that national parks in Scotland also aim to promote the sustainable use of the natural resources. To our eyes, it often seemed like promotion of local economic development took precedence over nature preservation.

Of course, the balance between preservation and sustainable use is a matter of longstanding and heated debate everywhere. In the US, in an oft-repeated tale, John Muir had a falling out with his friend and colleague Gifford Pinchot, first head of the US Forest Service. They engaged in a healthy debate over how to strike the balance until Pinchot publicly supported sheep grazing in forest reserves. The story has it that Muir reacted by telling Pinchot, “I don’t want anything more to do with you.”

We walked nearly 200 miles in the UK in these past months, almost always among ubiquitous sheep. Seeing close-up the devastating impact that these useful and often entertaining creatures have on the landscape, Muir’s reaction resonated deeply with us. Surely it was also driven in part by his boyhood in largely deforested Scotland where human settlements were cleared to make room for sheep. While you don’t find nature on a grand scale in the UK, the countryside has great pastoral beauty. Some of the landscape is even quite rugged and feels very remote.

I’m always surprised at how empty parts of this small island can feel. It’s slightly smaller than Michigan, Wisconsin, or Oregon, but home to more than three times the number of people in those three states combined.

One of the most remote areas we visited in the UK was the northwest Scottish Highlands—which oddly is not a national park. We were literally awestruck by the seemingly immense, rugged landscape, mountainous and coastal, sparsely populated by either humans or sheep these days. We would love to spend more time there, as we barely scratched the surface.

Forestry

Don’t expect large extensions of mixed old growth forests in the UK, although there are many small stands throughout the island. More common are patches of “forestry”—dense rows of pine or broadleaf trees clearly demarcated from the denuded surrounding countryside. These monoculture forestry plantations are the result of intense effort to increase the country’s strategic timber reserve after World War I.

Trees did grow all over the British Isles before they were felled by man—sometimes thousands of years ago. They could again, but it would take intense long-term focus to recreate bio-diverse environments.

We saw an example of such an effort on the Isle of Skye (not a national park); 17 years into the project there were only very small trees to show for it fighting valiantly to survive in thin rocky soils on windswept hills.

We found managed forests to be sterile and depressing in their complete lack of diversity of other plants, large or small, and utter absence of wildlife. (And by wildlife, I mean even chipmunks or squirrels, insects, and birds.) Scotland’s Cairngorms National Park is working to save tiny red squirrels, but in three days of hiking there, we never saw any. We did see fleeting glimpses of other campaigns focused on wildlife regeneration, but it’s difficult to imagine how they will succeed without diverse habitats.

It caused us to reflect on the biodiversity that still exists to some extent even in our new growth east coast forests. We often take this diversity for granted, but clearly shouldn’t. Once you lose it, it may be impossible to get it back.

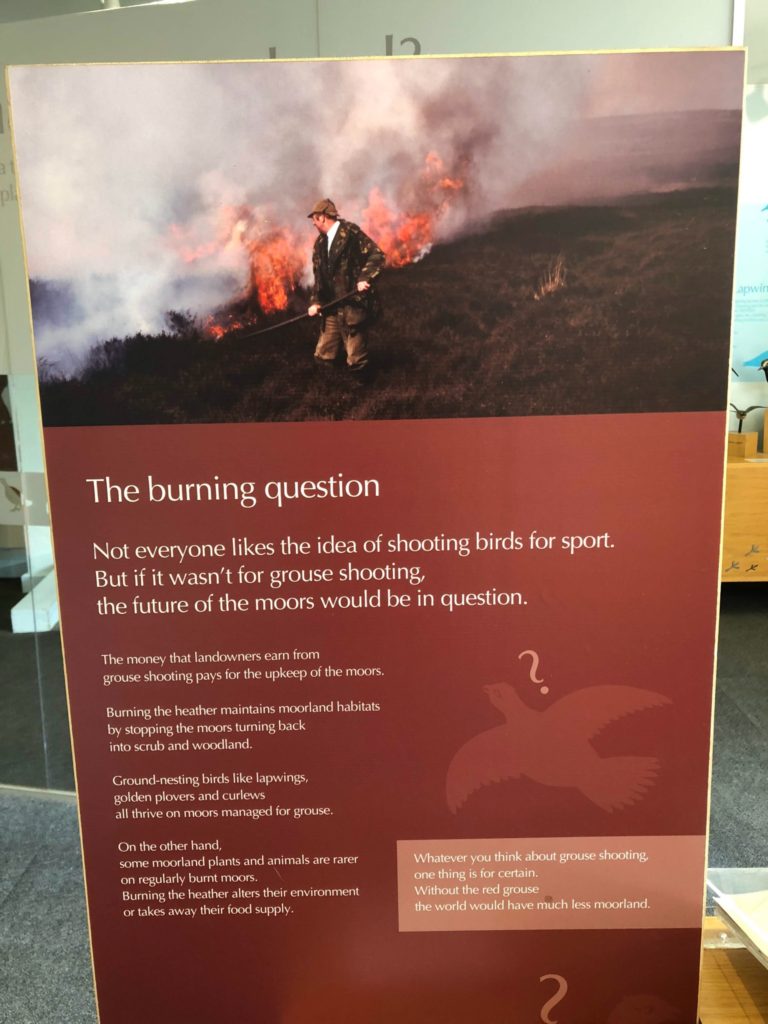

An exhibit in the North Yorkshire Moors visitor center makes the point that the moors are not natural, but rather man-made (the result of age-old deforestation), and they must be managed to keep them that way. The large private estates that own most of this stretch of moorland burn patches of it periodically to provide habitat for grouse hunting and stop the moorland from “turning back into scrub and woodland,” which would provide habitat for other wildlife. Hmmm…..

Not made for backpacking

While the UK could be described as a hill-walker’s paradise, the national parks are not so welcoming to backpackers. The exception is Scotland, which promotes not only the “right to roam,” but also the right to “wild camp” just about anywhere. We were told in visitor centers that camping is only allowed in designated campgrounds (often just a privately owned field where you can pitch your tent or park your RV). We also heard that rangers look the other way if campers are well-behaved and dismantle tents early in the morning, and we met backpackers prepared to flaunt the rule and trust to lax enforcement. We weren’t….

We found informative visitor centers in two parks in Wales with helpful staff and volunteers. In general, though, there is very little park-specific infrastructure. Since the government doesn’t own the land—and there is no dedicated “park entrance”—it’s impossible to charge an entrance fee. Instead, most parking lots in the parks compel you to pay for parking.

Many of the communities in and near the parks cater to tourists—with guest houses, restaurants, tours, etc., and some benefit from convenient rail links from the urban areas. You can also take a steam engine train to the top of Snowdon, the highest mountain in Wales, which contributed to cheek-to-jowl crowds at the summit. (For the record, we followed a tricky route that involved lots of “scrambling” in dense fog.) See Lorrie’s last blog.

We enjoyed our visits to the UK national parks and natural places. We relished the opportunity to breathe fresh air, experience true silence, and walk alone in beautiful landscapes, as we pondered the intersection of man and nature over generations, and how best to go forward.