I’ve been thinking a lot about remembrance lately. It’s partly about my dad, who died in January, and who I’ll be remembering with family and close friends next weekend. But I’ve also been thinking about public remembrance of traumatic events. These reflections are primarily prompted by how the people of Chile and Peru have faced the terrible abuses that took place in their countries in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. That doesn’t seem all that long ago because I remember well when they were reported as current events.

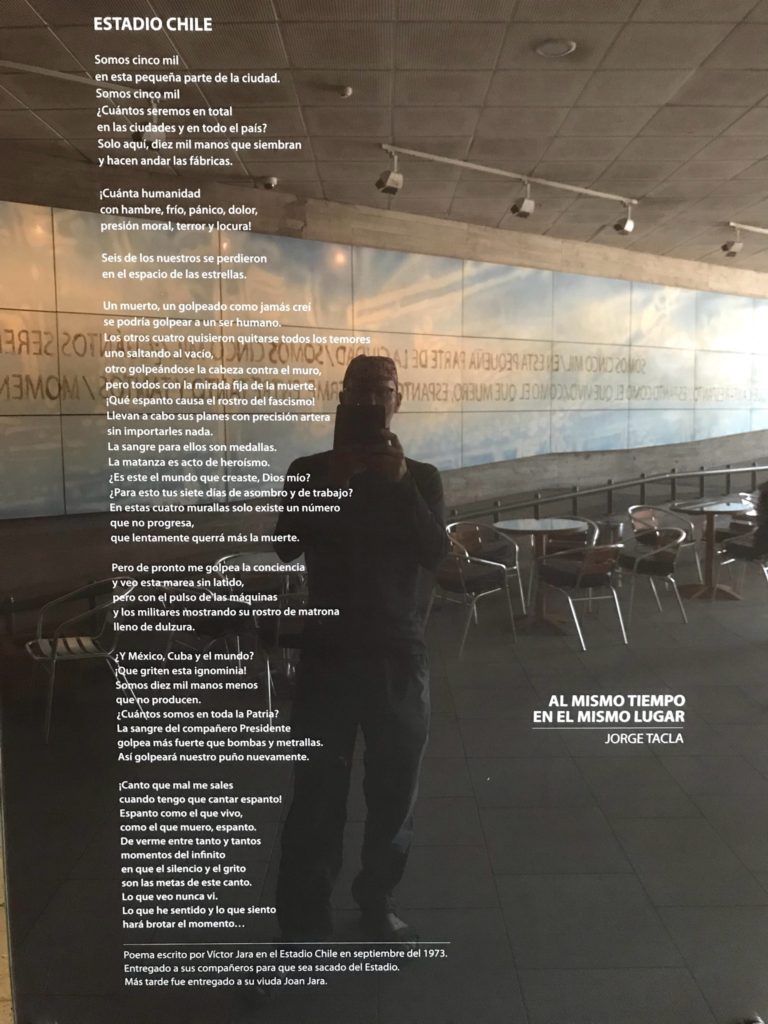

In late March, while we were in Santiago, Chile, we visited the Museum of Memory and Human Rights. With its extensive physical, video, and audio documentation, the museum provides an unflinching look at almost 20 years of state terror and human rights violations under the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. We came away exhausted and deeply impressed by the courage of the Chilean people to confront this painful period head on. The Pinochet period is a complex legacy that the museum handles with sensitivity and thoughtfulness. There were a few uncomfortable reminders of the role that the United States played in undermining the democratically elected Allende administration and supporting the military coup on September 11, 1973. But while there were outside influences, the atrocities pitted Chileans against other Chileans, with terrible consequences that are still discussed today.

After spending three weeks in the Cusco Region doing a deep dive into pre-Inca, Inca, and colonial history, we wavered on where to go next. The obvious “tourist destinations” would have been Lake Titicaca or the Colca Canyon. But we love the mountains, and we don’t like to spread ourselves too thin, so we decided to stay focused on Peru’s central Andean highlands–specifically, the Ayacucho, Junín, and Huancavelica Regions. Wow! We got a history lesson of a different sort.

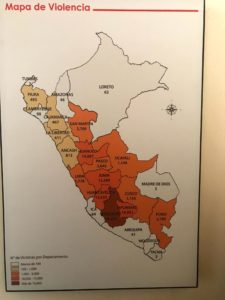

These Andean Regions were ground zero for horrendous violence in the 1980s and 90s by the Communist Party of Peru (Shining Path, or Sendero Luminoso) and its Peoples’ Guerilla Army that was matched or perhaps even exceeded by Peruvian military counter-terrorism forces. The Maoist Shining Path expected to find fertile ground for its violent revolution because successive national government administrations based in coastal Lima had long neglected these poor indigenous communities in the mountains. Indeed, the government ignored the armed uprising for three years before beginning repressive counter-terrorism operations. The Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, working in the early 2000s, estimated that nearly 70,000 Peruvians lost their lives during “The Violence,” killed by Shining Path or the Peruvian military, or to a much lesser extent the MRTA (another revolutionary movement) or community self-defense committees. Many more people were affected indirectly as family members, friends, or colleagues of the victims.

Shining Path got its start in the picturesque colonial city of Ayacucho, just a few miles from where the last battle for Latin American independence from Spain took place in 1824. The humble Museum of Memory in Ayacucho is housed in a single room above what used to be a soup kitchen for orphaned children of the disappeared. It was created and continues to be maintained by an association of mothers and wives whose loved ones were taken from them by the guerillas or the military, and it tells the story of the era in a very personal way. The museum contains pictures and personal effects of the victims, as well as newspaper clippings and a life-sized model of the room where military investigators tortured suspected collaborators. We found that horror is still very present for the people of Ayacucho, and we heard heart-wrenching personal stories most days we were in the city. Sitting in the busy central plaza–practically the only tourists around–we couldn’t help but wonder what memories each person carried with them. And as to the many young people around us who are too young to remember the period–how have they absorbed this legacy? At the same time, the people of Ayacucho exhibited a palpable sense of pride in their city. Our visit happened to coincide with the celebration of the 478th anniversary of the city’s founding, so we were also treated to days of parades and cultural celebrations, including fabulous music and traditional dances.

After nearly a week in Ayacucho, we traveled 160 miles by bus over a seven-hour cliff-hugging road to the much larger, sprawling and unattractive city of Huancayo, the capital of the Junín Region. This area also saw its share of Shining Path-related violence, and four years ago the Huancayo city government opened its own “Place of Memory.” This large museum with a four-story atrium also displays names, pictures, and personal effects of Hauncayo’s victims, including an exhibit about how the violence rocked the local university, affecting students and faculty alike. Our AirBnB host later told us that when his father was a janitor in the university, the military tortured, interrogated, and threatened to kill him (fortunately, he was later released).

Huancayo takes the ongoing impact of this trauma seriously and provides free counseling to victims who ask for it. Some of the museum’s exhibits ask visitors directly how each of us can play a role to ensure that similar atrocities are not repeated. Others point out the corrosive nature of other kinds of antisocial behavior, like corruption and discrimination, as well as the dumbing down of the press in favor of puerile entertainment that makes it more difficult for the public to hold leaders accountable.

The Huancayo museum also tries to place the violence in its larger historical, intellectual, and social context. White Spanish conquerors dominated what had been extraordinarily successful and proud indigenous cultures, including the Incas who had succeeded in uniting multiple Andean peoples within a vast empire stretching for thousands of miles. After Peru won its independence from Spain in 1824, the white descendants of Europeans prospered, living primarily in Lima and along Peru’s coast. Dark-skinned highlanders, on the other hand, saw few benefits from the state and lived in poverty. That’s why Shining Path thought it could succeed here and partly why the government’s military response was unable to distinguish guerillas from the terrorized indigenous people. Unfortunately, poverty and discrimination persist, and while the Peruvian economy has made enormous strides in recent decades, and poverty rates have declined nationally, the people of the highland areas still lag far behind.

From Huancayo, it’s a five-hour train trip to the picturesque mountain town of Huancavelica, meandering through beautiful Andean landscapes. We were warned repeatedly that it’s VERY COLD in Huancavelica, and they were right–you just need to keep your jacket and hat on all the time! The town, situated in a box canyon like the Telluride of Peru, was established by the Spanish to support the nearby Santa Barbara mercury mine that was so important to the Spanish quest for gold and silver. (Mercury is used to amalgamate gold and silver from the ore where they are found. Without this local source from the only mercury mine in the Americas until the mid-1800s, the Spanish would have needed to import it from Spain in order to exploit rich silver deposits in Bolivia and Mexico.) The mine did not translate into prosperity for the people of Huancavelica, however, and today this continues to be the poorest region of Peru. Here too the government’s neglect of these poor communities made them good targets for Shining Path, and they suffered terribly in the violence of the 80s and 90s.

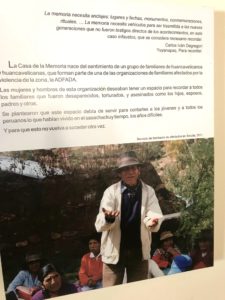

As in Ayacucho, Huancavelica’s “House of Memory” was established by a local association of the families of victims. It is housed in three dilapidated rooms in Huancavelica’s municipal library. It was closed, perhaps indefinitely, but I was able to persuade the caretaker to let us into one of the rooms. There were several frightening photographs of peasant women lined up against a rock wall detained by soldiers, and some gruesome photographs of dead bodies. In one, a small child squatted nearby eating. We learned more about how poor peasants were caught between Shining Path and the Peruvian military. The most powerful exhibit was a thick binder sitting on the table. Opening it, I came face to face with the most terrible thing I’d seen–a detailed accounting of every victim in the Huancavelica Region (almost 15,000 people) describing what happened to them, and whether the perpetrator was Shining Path or the Peruvian military. Some had their hands bound and throats slit; others were tortured and shot; still others were sexually abused. It went on for page after page after page. It was a relief–and pleasantly jarring–to come back out into the sunlight where a boisterous class of preschoolers were dancing in the plaza, laughing and clapping to traditional Andean music.

Chile and Peru are not the only places that have built museums to help us remember terrible tragedies. There are many holocaust memorials and museums, and I’ve been to a very moving genocide museum in Mexico City. Last year, Lorrie and I visited the Rosa Parks museum in Montgomery, Alabama, and the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, which is located on the site where Martin Luther King was assassinated. Both museums are very thoughtful and moving in how they remember the courageous work of those who fought for justice and civil rights in the United States. And I’ve read with interest about the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice that opened last month in Montgomery to help us remember the terror of racial lynchings and the legacy of slavery and racism.

With so many museums and memorials that exhort us never to allow such terror to rise again, can we truly say that we’ve slayed the dragons of past atrocities? Are they truly past, and now just painful memories? Can telling these stories help future generations to move in a more positive direction? Or can these places do little more than provide recognition and some small solace to those who have suffered terrible injustice? How can we bring the terrible message of these places alive to those who won’t visit, to those who deny that the atrocities are still relevant today, and to those who deny the atrocities themselves? How can we speak out and defend ourselves effectively against the bigotry, racism, and anti-semitism that is so prevalent in public discourse and social media? And how can marginalized communities strengthen their voices to help build a more just and equitable society, without resorting to violence?

I know these are all big questions with no easy answers. But these are the questions that have been running through my mind as we have immersed ourselves in this beautiful and fascinating part of Peru. It’s multi-layered, provocative, and complex.

We have been traveling for over a year now and are beginning to think about how we want to live after this glorious trip. (No announcements yet!) Travel always enriches the thoughtful traveler, and we will certainly be looking for opportunities to integrate and draw meaning and purpose from our time in the wide open natural spaces of the western United States last year, the rich and distinctive layers of cultural traditions in the Andes these last few months, or untold experiences yet to come in Europe later this year. Regardless, we’re both very conscious of how extraordinarily privileged we are by virtue of where we were born and the color of our skin. So many are far less fortunate.

Thanks Bob (and Lorrie). So well said — sharing so gently humanity’s woes, and efforts to triumph.

Very insightful and profoundly thoughtful, thank you, Bob. Reading your questions, I puzzle in dismay about our human nature: our capacity to crate with great ingenuity and tremendous effectiveness great science, beautiful and meaningful art and loving relationships but also senseless and immense pain and suffering for others and enormous and dispassionate destruction of our planet. You travel delving profoundly into nature, history and culture, bravo!

Eye-opening, and I don’t walk around blindfolded.